Last year I wrote a master’s thesis, which proved to be a pretty challenging experience. If I could go back in time and help out Sam-one-year-ago, this is the advice I would have given him.

I expect lessons 1 and 2 to be most be helpful to other beginner researchers in scientific or analytic disciplines, while lessons 3 and 4 probably apply to beginner researchers in general.

1) Don’t try to “make it work”

The goal of my thesis was to implement a method to solve a certain problem more efficiently than in previous work, or in other words, to “make the method work”1. I think this choice of goal has (and had for me) three undesirable side-effects:

-

It’s bad for mental health—because “doing well” means “making the method work”, which makes it easy to worry about failure every time it seems like the method might not work.

-

It discourages a curious, scientific mindset, and makes it harder to notice confusion2—because often, “following the evidence where it leads” and “being confused” are antithetical to “making it work as soon as possible”.

-

If the method fails, then the project is unlikely to make an interesting contribution. This is especially true if it’s hard to know why it failed—because in this case, it’s hard to say whether it’s due to faulty implementation, or the method not working in general.

What are some alternative goals? For my thesis, a goal of “gathering information about whether the method works, and then testing hypotheses to explain its success/failure” would have been a good bet. This is a subtle reframing, but it alleviates the three negative side-effects mentioned above:

-

“Doing well” only means “gathering information” and “testing hypotheses”, which, sure, are still tricky and failure prone, but don’t require betting on an uncontrollable outcome (the method working). It’s much easier to take steps that will lead predictably to success.

-

I claim that “following the evidence where it leads”, “noticing confusion” and other good scientific practices are the best strategy for succeeding at this kind of goal.

-

If the method fails, the hypotheses explaining the failure could inform future progress on the problem by suggesting possible improvements to the method, which is still an interesting result.

I think the idea of reframing a goal to have these three properties is similar to leaving a line of retreat, except applied to research goals rather than dearly held beliefs. Another way of stating it would be that it’s desirable to have research goals which fail gracefully. I’d be curious if anyone can think of general ways to do this kind of reframing.

2) Check all the baselines

I was aware of the advice that in interpreting results, it’s important to check the performance of baselines (i.e. simple/off-the-shelf/brute force methods), in order to know whether your new fancy method is actually making a contribution.

For one part of my problem, I checked two such baselines3, which ticked that box in my mind. However it turned out that there was another very simple method4 which (quite unexpectedly) solved it. I could have saved a week of meaningless experiments if I had spent a few minutes brainstorming other possible baselines before trying my method.

3) Don’t “try”

This idea is not my own, but I like it so much that I wanted to rearticulate it here. I’ll describe my implementation of the advice first, and then the problem it’s intended to solve.

When I’m working on a problem, I like to imagine that Yoda is sitting next to me. Every hour, he gently reminds me that there is no try, or in other words, that “I’m trying to do X” (or “I’m thinking about how to do X”) is rarely the best strategy for actually achieving X.

A much better strategy, according to Yoda, is to take low-level actions that you expect will move you closer to a solution. This strategy, he says, would help me avoid two failure modes I run into often.

Firstly, it ensures that my actions (towards a solution) are at the right level of granularity. For example, while working on my thesis, I once had to admit to Yoda that I was “trying to apply an active learning algorithm in the setting of RL from preferences”. And as he predicted, this resulted in nothing more than two hours of chewed pencils and staring with ponderous visage into the distance. More effective (lower level) actions could have been:

-

“I’m searching Google Scholar to see if anyone has applied active learning in this setting before”, or

-

“I’m confused about whether I should treat the problem as classification or regression, so I’m resolving that confusion by writing down examples of both and seeing which one fits my intuitions better”.

Secondly, it ensures that I’m clear how my actions will move me to a solution. For example, Yoda once caught me setting up an experiment without knowing how the outcome would actually provide evidence for or against the hypothesis I was testing (because, on reflection, the experiment’s possible outcomes were equally likely regardless of whether the hypothesis was true). This action was sufficiently low level, but I had flinched away from the work of checking whether it was actually a helpful action to take.

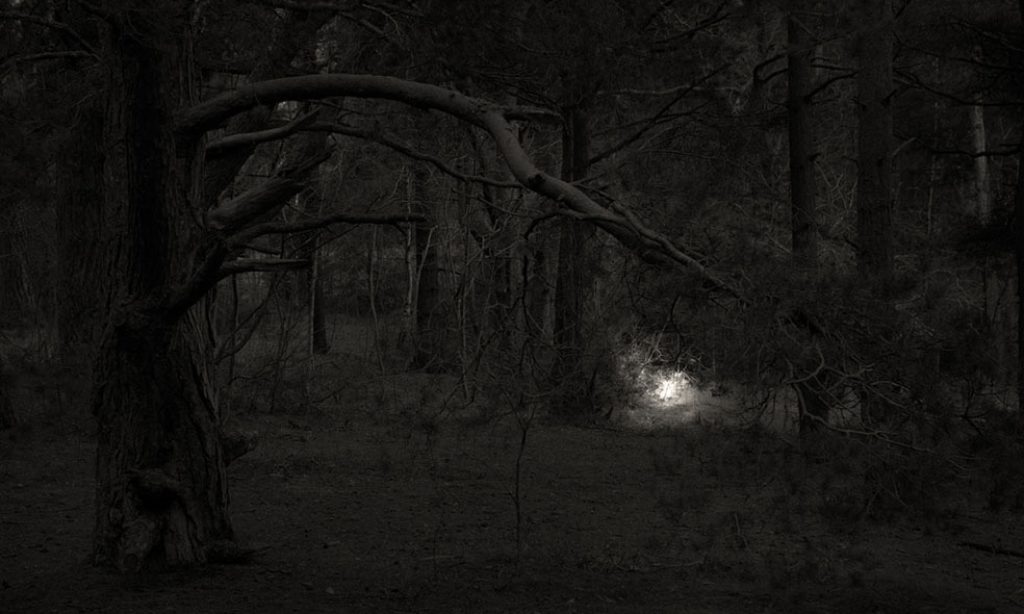

4) Beware the will-o’-the-wisp!

In English folk tales, the will-o’-the-wisp is a ghostly light, seen by travellers at night. Because it recedes as travellers approach, it earned an infamous reputation for leading astray the curious or confused. Apparently, it might look something like this the image at the top of this post…

In my nighttime travels through the treacherous terrain of RL, I was enticed by two such receding targets. Firstly, I intended to get in touch with the authors of a related paper, which I expect would have resulted in some invaluable guidance. Before doing so, however, I felt a need to “prove myself” by making a solid start and “having something to show for it”. But of course, the target of “having something to show for it” receded as I approached—and so I never sent the email.

Secondly, I was enticed by the light of “being seen to be making good progress” by my supervisor. So, when I inevitably encountered setbacks, I avoided checking in until I was “back on track”. But of course, by the time I’d resolved the setback, the criterion for “back on track” had moved along, and so I worked furiously to try to catch up. Sometimes this worked, but more often I got stuck again while chasing that target, and the cycle repeated—until I was “embarrassingly” behind and hadn’t spoken to my supervisor for weeks.

What could I have done differently? If I had pre-committed to sending the email at the end of week 3 of my research, or pre-committed to regular check-ins with my supervisor, then I wouldn’t have wasted energy chasing those receding, ghostly lights.

-

For those who like concreteness, the problem was deep RL from human preferences, and the method was to query the human for their preferences about the agent’s behaviour that would be most informative, rather than querying at random. ↩

-

If this term is new to you, the ability to “notice confusion” means: when you see something odd - something that doesn’t fit with what you expected, given your other beliefs, being able to promote this realisation to conscious attention and think “I notice that I am confused” (explanation borrowed from here). See these posts for lots more about that! ↩

-

Concretely: using a randomly initialised policy, and making queries to the human uniformly at random. ↩

-

Concretely: using a randomly initialised reward model. Unbelievably, for several of the random seeds I tried, training a policy on the rewards from a random reward model solves the Acrobot environment in OpenAI Gym. ↩